Event: Evolving Models for Senior Housing and Care in New York City

Location: Center for Architecture, 01.19.12

Speaker: Judy Edelman, FAIA, & Andrew Knox, AIA — Principals, Edelman Sultan Knox Wood / Architects; Peter Samton, FAIA, & Susan Wright, AIA, LEED AP — Principals, Gruzen Samton – IBI Group; David Weinstein — Executive Vice President/Chief Operating Officer, The Hebrew Home At Riverdale

Moderator: Christine Hunter, AIA, LEED AP — Principal, Magnusson Architecture and Planning

Organizers: AIANY Design for Aging Committee

The Reingold Pavilion at the Hebrew Home for the Aged in Riverdale.

Gruzen Samton – IBI Group

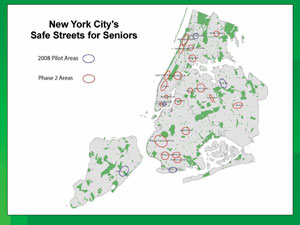

Living in NYC has its health benefits. At 80.6 years, life-expectancy is now higher here than in the rest of the country. And, according to statistics, the city’s senior population will significantly increase over the next two decades. Approaches to designing facilities for senior living have evolved over the last 50 years. The major goal now is to prolong the length of time that seniors are able to remain independent, which is what most seniors want, and to which many design details can contribute. To illustrate this, Judy Edelman, FAIA, and Andrew Knox, AIA, of Edelman Sultan Knox Wood / Architects, presented their work on several HUD-202-financed, mid-rise, affordable residential buildings. Susan Wright, AIA, LEED AP, and Peter Samton, FAIA, principals at Gruzen Samton – IBI Group, spoke about their work on the Hebrew Home for the Aged in Riverdale with COO David Weinstein.

In HUD-202 buildings, many seniors live alone in their own apartments. As they age, they may require increased levels of assistance and more companionship. Edelman and Knox emphasized the need for having social and medical services available within their buildings, along with the added benefits of mixed uses, including retail space, cafés, and services for other age-groups such as day care centers. To draw people out of their apartments, lobbies are designed as social “hang-outs” for seniors, adequately sized, with comfortable seating, daylighting, sufficient artificial light for reading, bright colors, interesting floor materials, and plants.

Security guards can be social lubricants if their stations are designed in convenient locations so seniors can engage them in lively conversation, according to Edelman and Knox. If constraints limit the size of the lobby, other gathering spaces should be provided within the building. Roofs may be used as recreational spaces. Color can aid wayfinding. Patterns in corridors can indicate directions and minimize the perception of distance. Edelman and Knox have found the most preferable windows are the swing-out awning type. They are easier for seniors to operate than double-hung or sliders, and they allow good views looking toward the street — “where the action is!”

The Hebrew Home for the Aged is a large facility housing 1,000 residents, 15% of whom live independently and 85% who require some level of assistance. The home is located on a 16-acre campus organized into 21 “neighborhoods” with varying levels of care. The major reason residents choose to live at the Hebrew Home is that the range of care permits residents to move easily from one part of the facility to another as their needs change. A multiplicity of activities attracts residents to the more public spaces.

When the Hebrew Home purchased the facility from an orphanage in 1948 it consisted of several discrete buildings. Over the years, as Gruzen Samton designed additional buildings beginning in 1964, the facility has become interconnected via a central, ground-level interior concourse and corridors on other floors. Wright, Samton, and Weinstein emphasized that their goal is to promote an intimate, small-scale, home-like atmosphere that encourages the greatest amount of independence possible for each resident. The newest building, the Reingold Pavilion, provides more private space per resident than previous buildings. It consists solely of single private bedrooms with full baths and showers. These are grouped into 10-room clusters, each located around a central gathering/recreational space. Small dining spaces accommodate two clusters, and waiters serve the residents as in a restaurant. Earlier buildings had double bedrooms and much larger dining spaces, presenting a more institutional ambience; they are being redesigned.

These are two different types of facilities designed to accommodate the special needs of seniors, yet there are similarities in their overall approach and in many of their details.

Jerry Maltz, AIA, is the co-chair of the AIANY Design for Aging Committee.